Helene (Leni) Riefenstahl: A Fascist or Merely a Filmmaker?

In case you had recently watched Munich, Steven Spielberg’s 2005 action thriller, you’ll recognize the dialogue featured in the image below:

But who is Leni Riefenstahl that Robert suspects to be the “old lady upstairs”? And why would he desire to kill her? In fact, it is quite impossible to mention Leni Riefenstahl’s name without getting into the controversy around her, and around the two films she made prior to the lapse of her career after the Second World War.

A Controversial Filmmaker Par-Excellence

Try typing “Most controversial German filmmaker” on Google search, and only one name will pop up: Leni Riefenstahl. To some, Leni Riefenstahl had earned, as filmmaker Gordon Hitchens puts it, “an undisputed top rank among the all-time documentary filmmakers of any nationality.” To many, nevertheless, what Riefenstahl is widely remembered for, is her work as Nazi propagandist.

In his book The Wilson Quarterly, Steven Bach argues that “to her admirers, Olympia and Triumph of the Will are works of auteurist power, innovation, and beauty; to her critics, they are propaganda for a murderous regime…That they might be both seems self-evident, but no such summary evaluation of them has ever taken hold because Riefenstahl has so successfully shifted the focus of the debate to herself- as a seeker of beauty and a political naïf.”

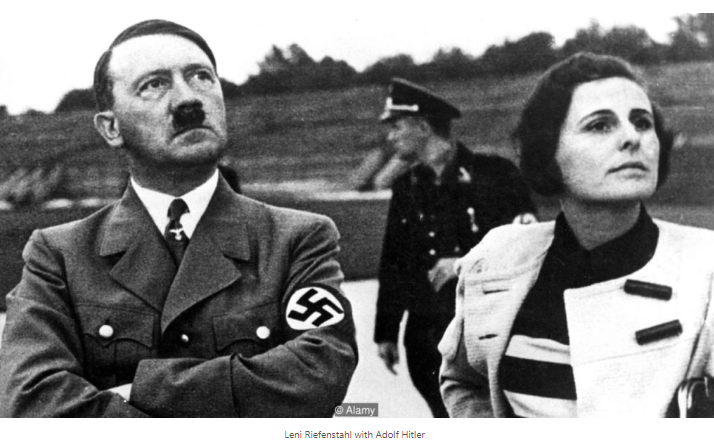

By the end of World War II, Riefenstahl had to pay the hefty, but natural, price for the art she had granted the unethical regimen she had served. She became universally loathed and internationally boycotted. The Economist highlights the controversy around her career: “Not even Albert Speer, with all his grandiose architecture cast in marble, came as close to capturing the subconscious allure—at once both devilish and erotic—that represented power to many Germans in the early 1930s”.

The Early Days of Leni Riefenstahl

Before the Nazi era, the Weimar culture, characteristic of the interwar period, dominated the arts scene in Germany. During that period of time, Germany, particularly Berlin, was a fertile ground for arts and innovation. Leni Riefenstahl had thrived in that scene. After working as a dancer for a while, she made a name for herself as an actress and a director in the popular German genre of “mountain films” that is often comparable to American westerns. She was taking, performing and creating roles that were so challenging to pull off on screen, especially with the lack of today’s special effects and technology. For instance, in the film where she debuted as a star, Der Heilige Berg (The Holy Mountain) (1926), she had to perform on a steep rock face and be buried by an avalanche. “I had to cling onto a rock with my hands, until the avalanche came down.” Leni lets out a laugh as she continues, “Not just once, but two or three times. People today say it was madness but (Arnold) Fank demanded our all.**”

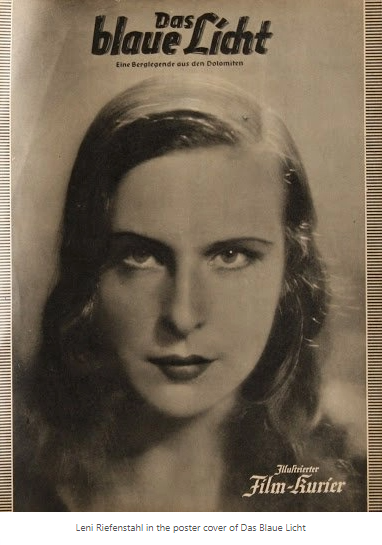

In her directorial debut, Das Blaue Licht (The Blue Light) (1932), it was the first time Riefenstahl had to wind a camera. The moment she began to turn the handle to shoot, there was a terrible bang. A torch exploded, and her face got burnt. But she went on filming despite the pain and finished the shot. She could not notice that her face was burnt until she looked at the mirror after wrapping the shot. Leni’s directorial debut reportedly became Hitler’s favorite.

The mountain films, to which Leni was associated, became regarded as an indigenous national genre of her time. Based on Alexander von Lünen, this genre was “dear to the Nazis and other nationalists in Weimar Germany who saw mountaineering – man’s struggle with nature – as both a symbol for Germany’s post-World War I struggle and the social-Darwinistic model of the survival of the fittest.”

Riefenstahl’s Involvement with the Nazis

Riefenstahl came to documentary filmmaking at a time when the politicization of the form was a trend. As soon as Hitler came to power in 1933, Joseph Gobbles, his Minister of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, poured his effort into controlling media. Under Gobbles’ control, censorship was promoted as positive and he, therefore, ended up taking charge of all the details of production, display and distribution. This had led to a catastrophic decline of film and its qualities under Nazi Germany. Erik Barnouw, in his classic “Documentary: A History of Nonfiction Film”, however, refers to Leni Riefenstahl’s work as an “exception: the work of one genius who – due to unusual circumstances – flourished outside the Gobbles dominion.”

Hitler was a notable fan of Riefenstahl’s work. Only months after taking control, and days before the annual rally of the National Socialist German Workers Party, he called her checking on the work he had assigned her. She had been unaware that Hitler had ordered his Propaganda Ministry months earlier to appoint her with a film about the rally, but Hitler insisted that she proceeds. She rushed to the rally with few equipment and little assistance.

Resentful at being bypassed, Gobbles turned her experience into a nightmare. Albeit not so proud of the outcome, she completed the party’s short Victory of Faith. Leni often gets inflamed if the subject of this film comes up. “We only filmed a few meters before we were interrupted,” Leni says. “The Party didn’t want us to make the film despite Hitler’s commission.*” She strictly denies the film any association with her technique or artistic vision. “I hardly did anything on it,” Leni claims. “It was just a few shots I put together, because Hitler wanted it**.” Until recently, the film was thought of being lost and many doubted that it had ever actually been made.

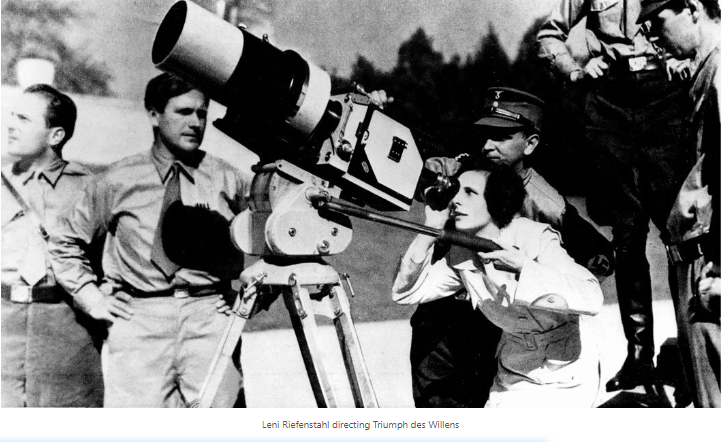

Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will)

Until this day, Triumph of the Will is regarded as the best propaganda film of all time. Riefenstahl proclaims that “You can only discuss technique in Triumph of the Will”**. According to her, Triumph of the Will is the one- and only-Party Congress film. “Never two or three. Just the one.”

Months after Victory of Faith, Riefenstahl was contacted again by Hitler for the party’s 1934 rally, promising that, now, she’ll receive all the time, support and equipment she needs for this to be the largest ever staged film. The outcome ought to be an announcement to the whole world of German’s rebirth. Measuring on her previous experience, Riefenstahl turned the project to the renowned Walther Ruttman of Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City). Although a leftist at the time, Ruttman was excited to do the project inasmuch as he drafted plans and started shooting footage. But Hitler insisted Leni does the job. To commit, Leni had her nonnegotiable terms: (1) not Hitler nor Gobbles are to interfere; (2) no one can see the film until it was ready to screen; (3) the film had to be made by her company and not by the Propaganda Ministry.

Leni Riefenstahl maintained that the making of this film was just a job that she mastered to perfection. “I wondered what could I do to make it better than the news reels?**” Her answer was to avoid repetition and static cameras, and to come up with mobile camera movements. Erik Barnouw confirms that “never had there been a mobilization and deployment of resources – men and gear.” To accomplish her mission, Leni Riefenstahl had appointed 120 crew members, 30 cameras and 4 sound trucks.

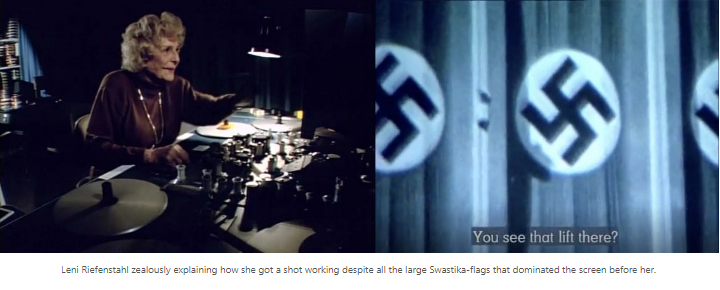

The town of Nuremberg, where the rally was scheduled to take place, became a construction site, propped, according to her specifications, with distinct ramps, towers and bridges. She took into account every shot size and every camera angle, when building her structures. Flagpoles got equipped with an electric elevator. Vehicles with extension ladders were under her disposal so that cameramen could fly over the town and take the marching troops and their banners. Platforms and dollies were built, to capture the troops along with the Fuhrer. In fact, the looming close ups of Hitler were the first that the German people had ever seen.

Riefenstahl treated the film more like a musical composition. It took her five months, working on daily basis for 15 to 20 hours to get the flow right. “Either one makes a news reel, and those were made,” Leni indicates, “or one can try to make the material into a film that’s more interesting and without posed shots.” She aimed to let the impact of film derive from her “choreography of images and sound,**” without interfering with the event or the content of it. Unlike the typical newsreels or propaganda films of the time, Triumph of the Will has no one explaining the significance or the value of the occasion. Riefenstahl considered any commentary an enemy for film.

Triumph of the Will received the Best Foreign Documentary in Venice Film Festival in 1935. It also won a gold medal for its artistry at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. According to the Economist, the film has “sealed her reputation as the greatest filmmaker of the 20th century.” Later, congresses were filmed by other directors but they have long been forgotten.

Olympia

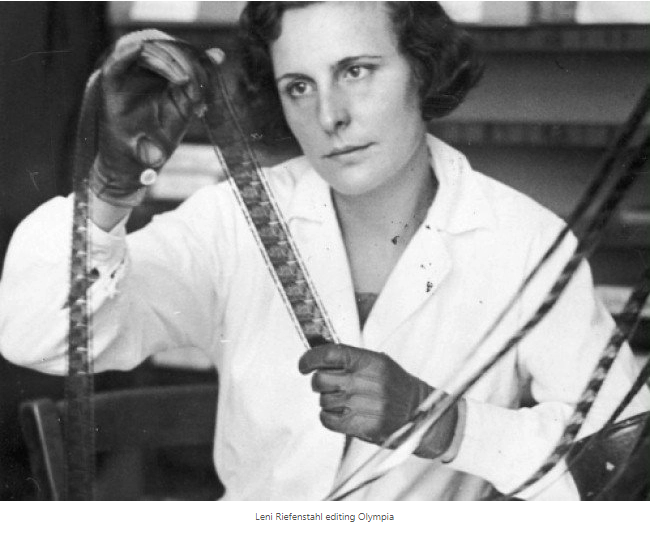

Driven by the success Triumph of the Will had gained, Leni proposed to do a film on the Olympics taking place in Berlin that year to the Universum Film AG (UFA). It was declined and ended up financed by a smaller company named Tobis. Another Olympics film was being produced by The Propaganda Ministry at the same time. Leni kept facing the same resentment she previously faced from Gobbles. He, according to Barnouw, “forbade leading camera men to work with her; at some point, ministry employees tried to bar her from the stadium.”

In an interview Leni did with Gordon Hitches, she declares that “the film’s theme was Schönheit – the grace and beauty of the body, of no propaganda purpose.” Although, the torch that is handed from one runner to the other, from Greece to modern Germany, and into a vast stadium presided by Adolf Hitler seems to suggest him as the owner of this “torch of civilization”.

Olympia generated two feature length films: Part One and Part Two. The natural beginning of Part One reminds of the beginning in Triumph of the Will and also of Leni’s early mountain-film career; conveying the atmosphere of classic Greece. Part Two, on the other hand, begins with the Olympic village, “the only place for it,” Leni explains to Hitchens. “I am the visitor to the Olympics . . . never tire the visitor.”

Numerous techniques we now see in sports reporting are thanks to her Olympia movies, such as following athletes on the tracks via dollies and underwater cameras in the swimming and diving competitions.

Contributions and Novel Techniques

Riefenstahl’s films paved the way to a school of thought that was never approached in documentaries before. Treating a documentary film like an architectural project, planning for the shots on site, and maintaining laws of balance, were all techniques unheard of prior to Triumph of the Will. She was the first to treat a visual composition like music. She relied on the power of the image’s rhythm rather than commentary. In her interview with Hitchens, she explains how she implements musical rhythm and alternates tension with relaxation for both sound and picture: “When one is up, then the other is down.”

In Olympia, one of her most startling innovations was how she filmed the diving sequences. Her use of slow motion to convey impact and action in sport activities was another technique she was the first to apply. She also developed her own technique in filming the dives, as they were followed through the air and under water in one shot. In fact, Barnouw observes how “the start of the dive was photographed from the surface of water; at the moment of impact, the cameraman went under water with his special camera while changing focus and aperture.” She also came up with diving beauty shots that challenged gravity. She utilized these shots as a long succession of dives that occasionally overlap with dissolves.

Both of her films were mostly shot silent; sound elements were added later. In both films she relied on a Wagnarian opening that gives a musical impact and sets the stage for the film. The use of extremely high and low shooting angles, panoramic aerial shots, and tracking shots for nonfiction were first seen in her films.

Perhaps the most significant contribution Leni Riefenstahl made is related to the genre that she herself refuses to be associated with: the propaganda films. With or without her awareness or even recognition, she proved that the power of cinema can be extremely dangerous. The films, she is remembered for, succeeded in uniting many to a deadly cause. Her role to that specific contribution, is deemed unforgivable.

*Areeb Zuaiter is a visual storyteller, a contributing writer, and an adjunct professor based in Washington DC. Her work focuses on identity, social issues, film and its history along with supporting rising filmmakers.

**Taken from an interview in the German documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl (Die Macht der Bilder: Leni Riefenstahl) directed by Ray Müller (1993).